Drawn from Courtly India

DRAWING AS BLOSSOMING

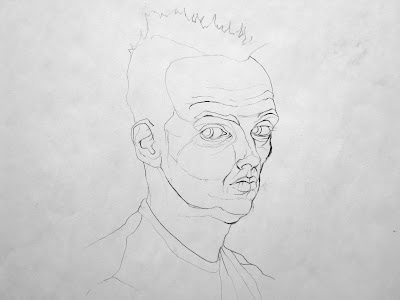

While each painting workshop in courtly India had slightly different techniques, the basic elements of the drawing process were shared. An artist began with a prepared sheet of handmade paper, which he burnished. The initial line was created in charcoal, black ink, or red ochre to introduce the suggestions of form and composition, either drawn freehand or using a guideline pounced from another picture. This first touch was strengthened with black or gray ink, following the initial line while also allowing for slight alterations in form. Corrections could be made by painting white pigment over a particular area where the line was to be reconsidered and redrawn. Once the composition had been established, the paper was burnished again, usually with an/agate stone. A white wash primer was often used to coat the entire sheet, smoothing the establishing brushstrokes and filling any voids in the paper. With the initial line still visible, the drawing could then be rearticulated and strengthened with black ink. At the same time, detail was added to the composition, often followed by color notations (either written or indicated through dabs of pigment) to instruct artists at the next stage. Pigments were mixed to achieve desired shades; brilliance and adherence were enhanced with a temper of (gum arabic) Color was applied in a slow, additive process, with each layer being given time to dry before the next was added. The coloring was often done sequentially from top to bottom) starting with the broad swaths necessary to fill the background of the composition. Color was added to the main figures last, bringing life and movement to the work. The addition of gold-either in a powdered form that was burnished to help adhere it to the page, or as gold leaf delicately glued to the finished painting's surface-completed the work.

A picture worked from start to finish in this fashion is generally regarded as a painting, but the process was not only driven toward one end result. In fact, works regarded as drawings can exist almost anywhere alone the continuum, including stages of coloring. A late eighteenth-century drawing from the Pahari court of Guler, A Nobleman and His Family Seated in a Pavilion (plate 2), exemplifies this idea. The delicately rendered figures and beautifully articulated composition reveal the working and reworking that can be considered the building blocks of a painting. The pillars of a pavilion frame the central figures as well as the lush landscape setting. The husband, wife, and small playful child were delineated first, followed by the landscape. A delicate(red line) the initial line added to the page-remains visible even with the additional layers of(ink, white wash, and (color.) The artist's reconsideration of this initial line is clearly visible in the figure of the demure wife, where a black line subtly varies from the underdrawing. Further changes to both stages can be seen where white wash ground has been added to correct areas of the composition, most noticeably in the young figure in the foreground and the female attendant to the left (see detail on p. 29). The background architecture of the pavilion is visible through her form, demonstrating that the figures were added after the composition was fully conceived. This is not to say they were added significantly later in the process, only that they were not blocked out in the initial drawing. The artist's practice of working and reworking continues in the next step in the painting process with the addition of color to the foreground and landscape. The landscape is covered in a wash, establishing the initial layer of color that, despite its light touch, obscures the drawn details of the trees and bushes. Further changes to the composition can also be seen along the upper border, where the cusped arches of the pavilion have been lowered to create a more intimate family setting.

Ananda K (Coomaraswamy)compared this reflective, additive artistic process to the blossoming of a flower; as color is applied, it reveals that which is "both shown and unshown." Many works from the Pahari region survive suspended in this "blossoming stage." Women Playing Music on a Terrace, from about 1820-30 (fig. 1), for example, has progressed from the light wash of color added to the background to a fuller, more robust opaque watercolor. Distinct layers of details have been added to the trees in the background, where the artist has painted first the shadows, then the individual leaves, and finally the colorful flowers. The heavy clouds above a bright orange sunset are also fully painted, drawing attention to the lightly sketched figures in the foreground. Though it is more finished than A Nobleman and His Family, this work, too, is "blossoming"; it survives not as a discarded, unfinished painting, but as a work that was valued and preserved precisely in this rich state of becoming.

If the act of drawing can be understood as a flowering of form, meaning, and experience, then understanding the process by which drawings are made is fundamental to seeing and knowing them more fully. In the following sections, each stage of a drawing's creation is examined: The present section assesses the role of artist and patron in forming a workshop and encouraging its output; "Paper, Ink, and Brush" and "Realms of Color" read meaning into subtle variations in tone; "Reuse, Repetition, and Reinvention" explores the role of innovation within the confines of the workshop system; and "What Line Reveals" examines subtle characteristics particular to certain artists and workshops. The drawings in the Conley Harris and Howard Truelove Collection speak to all of these ideas. Their enticing details reveal much about specific acts of making, yet they also tell a larger story about the importance of drawing-not only in the production of paintings, but as an art form.

%20-drawing_detail1494.jpg)

Comments